|

Thomas M. Barker and Paul R. Huey, eds. The 1776-1777 Northern Campaigns of the American War for Independence and Their Sequel: Contemporary Maps of Mainly German Origin (Purple Mountain Press, 2010. Pp. 208. illustrations, notes, bibliography, index. Hardcover, $49.00). In Don Quixote Miguel de Cervantes writes, “Journey all over the universe in a map, without the expense and fatigue of traveling, without suffering the inconveniences of heat, cold, hunger, and thirst.” [1] Thomas M. Barker and Paul R. Huey’s book is reminiscent of this quote. The 1776-1777 Northern Campaigns of the American War for Independence and Their Sequel transports readers both into the past and to German archives all from the comfort of their own home. In doing so, the authors have enhanced Revolutionary War historiography. They offer a visual perspective from Britain’s German auxiliaries that American and Canadian scholars and students rarely see. Forty-two maps, the vast majority of which come from Hessian and Braunschweig (Brunswick) archives in Marburg and Wolfenbüttel, respectively, compose the heart of this book, which is essentially an atlas. The remainder comes from various United States repositories, such as the Library of Congress, the New York State Library, and the Bennington (Vermont) Museum.

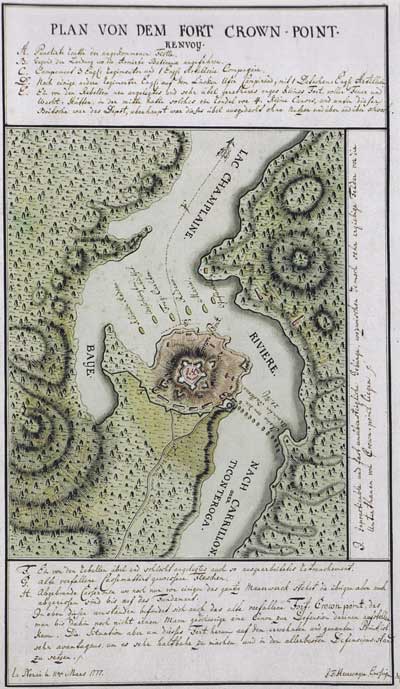

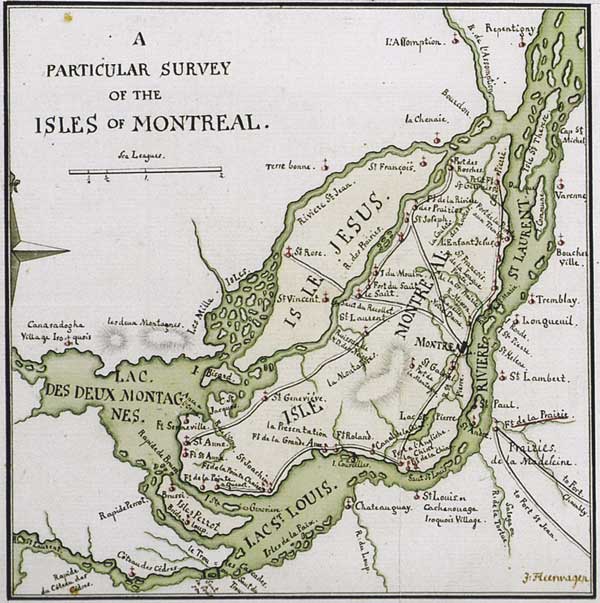

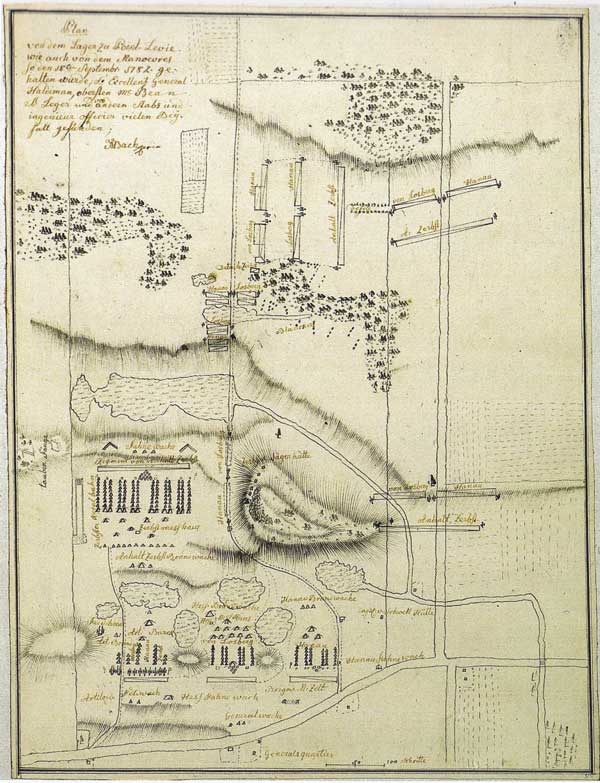

Barker and Huey open their work with a brief overview of the German troops who Britain hired to help suppress the American rebellion, mainly focusing on those sent to Canada. The authors stress that these soldiers were not “[m]ercenaries…the leased thugs or ‘guns-for-hire’ of the Renaissance epoch,” despite American propaganda to the contrary (p16). Rather, they were auxiliaries, whose employment by other powers was a widespread European practice. Barker and Huey further explain that most of these German troops actually volunteered for service, rather than being tricked or dragooned into the military. Additionally, the authors examine whether various German states helped or hurt themselves by “renting” their forces. They conclude that the practice benefited Hessen-Cassel and Braunschweig because British gold placed them on firmer financial ground and helped develop industry. Having established this background, the authors then divide the book into three chronological sections. The first and shortest part, “Background Maps,” is exactly what the title says; four maps that depict New York and New England. The second and longest section, “Maps of German Origins,” makes the book noteworthy. This traces the Germans’ path from their arrival at Quebec in Spring 1776 to their surrender with General John Burgoyne’s army at Saratoga in October 1777. This section contains thirty-three maps, such as “A Particular Survey of the Isles of Montréal”, “Plan of the Fort Crown Point”, and “The Mohawk Wood Creek Zone near Fort Stanwix.” The final section, “The Sequel” examines German deployments in the Champlain Valley and Canada from Fall 1777 through 1782. The book’s last map is a particularly interesting depiction of a mock battle conducted at Pointe Lévis. This demonstrates that the German troops continued to train for combat even after active campaigning ended. Barker and Huey include an excellent appendix which reproduces twenty-four of the maps in color, along with illustrations of various German leaders, and nine images from the Friedrich von Germann collection. This book has more to offer than just its visual images, however. The authors provide a heavily documented overview and commentary for each map, filled with a tremendous amount of information on a myriad of topics, not all of which are military. These range from the 1775 American invasion of Quebec and subsequent expulsion from the province to the origins of the New York - New Hampshire border dispute over the Hampshire Grants (Vermont). Barker and Huey also include both Native and African Americans in their analysis. They cover Catholic missionary activities among the Native Americans, the movements of the “ethnically-mixed Caughnawagas,” and the Indians’ roles during the campaigns (p52). Furthermore, the authors note the Germans’ employment of young Blacks as drummers. In the latter case, “[t]hey were taken back to Germany as a novelty for the public’s delectation” (p172).

A number of definite themes appear in the narratives and their accompanying notes. First and most obviously, Barker and Huey are not only interested in maps, but in the men who drew them. They provide biographies of a several German officers, such as Johann Michael Bach, who was seriously wounded at Bennington, skilled artillerist Georg Paeusch, and Carl Winterschmidt, who later defected to the Americans. Educated at military academies and a drawing school, these cartographers employed their considerable talents to craft detailed maps for operational purposes and to inform their curious sovereigns about their activities. This explains why so many of these maps ended up hidden in archives rarely visited by those from this side of the Atlantic. The authors also highlight the career of another gifted cartographer, Franz Pfister, a German-born former officer in the 60th Regiment, the Royal Americans. A protégé of Lord Jeffrey Amherst and Sir William Johnson, Pfister settled near Hoosick, NY, and declined an offer to design the American fortifications near Saratoga that Thaddeus Kosciusko later constructed. Instead, he suffered a mortal wound while fighting for the royal cause at Bennington. Pfister’s example, one of several Royal American veterans who appear in the book, reinforces the recent scholarship on the international nature of the regiment. [2] The book addresses the relations between British and German troops during the northern campaigns, suggesting that traditional accounts overstate the tension that existed between them. A “pan-European aristocratic way of life or elite class value system” united the officers that allowed them to cooperate and ameliorate disputes between the rank and file (p71). Still, Barker and Huey graphically illustrate the source of some of these tensions in a map of Ile-aux-Noix. While British troops occupied dry ground, their German counterparts encamped on swampy terrain, where “the proximity of snakes, bears, and howling wolves did nothing to ease their discomfort” (p71). The authors hint that Anglo-German relations deteriorated from General Guy Carleton’s tenure as commander in 1776 to that of Burgoyne’s the following year. By early October 1777, even before the defeat at Bemis Heights, some German officers complained about the army’s sorry condition, even while Burgoyne remained popular among British troops.

The 1776-1777 Northern Campaigns has a number of real strengths, starting with the authors’ thorough command of their material. They not only identify who drafted each map, when, and then give its dimensions, but Barker and Huey also frequently note the other maps that the cartographer based his work on. As a result, readers can trace the diffusion of ideas and information among the officers. The maps’ rich details provide readers with numerous new insights into the northern campaigns and the geography and settlement of New York, New England, and Canada. These details might be potential mill sites on smaller streams in the central-lower Mohawk Valley or two nuns’ boarding house and school in La Prairie-Sainte-Magdeleine. Historians and students interested in Valcour Island will find this book’s five maps and charts on the engagement especially worthwhile. These include two detailed orders of battle, a “Status of the Royal and Rebel Fleets on Lake Champlain,” and tactical maps of the engagement and its aftermath. Maps relating to Hubbardton, Bennington, and Saratoga will similarly aid those studying the 1777 Campaign. Finally, Barker and Huey have also compiled an extensive annotated bibliography, which will benefit other researchers. The inclusion of German language sources and discussions on the relative value of various translations are especially welcomed, as are the appearance of a number of websites in the footnotes. The book does have some rough edges, however. Anyone reading this somewhat oversized text would be well advised to have a strong magnifying glass and a large dictionary nearby. The small black and white maps are extremely difficult to read, as are some of the color ones, even though they cover an entire page. This is especially true when trying to locate the specific sites described in the maps’ legends. Similarly, the authors possess an extensive vocabulary and do not hesitate to employ it. Such terms as “pestiferous Saint-Jean,” “exogenous entrepreneurs,” and “lacustrine waters” make some of the sentences unnecessarily long and complex (pp49, 58, 167). The book contains a number of typos and small editorial errors, such as misnumbered footnotes, and its table of contents fails to list the page numbers for the various maps. Still, these are relatively minor inconveniences considering the overall value of bringing such rare maps to light. Those interested in military and social history, geography, and cartography will benefit from The 1776-1777 Northern Campaigns. One can only hope that Barker and Huey or others will compile a similar book on German maps from the Mid Atlantic and Southern campaigns.

Michael P. Gabriel, PhD. 2. Alexander V. Campbell, The Royal American Regiment: An Atlantic Microcosm, 1755-1772 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010). [return to text]

|